BIRMINGHAM: 'GODMOTHER' OF ALBERT IN PICARDY

After the First World War many British towns and cities became involved in ‘adoption’ schemes to provide help for the devastated battlefield. Many of the places adopted were on the Somme and Birmingham adopted Albert in 1920. Today Albert still has a ‘Rue de Birmingham’ and the almhouses paid for by the citizens of Birmingham still exist although with a different use.

In April/May 2008 my article on the ‘twinning’ was published as ‘Birmingham: Godmother of Albert in Picardy’ in ‘Stand To!’, the journal of the Western Front Association (no 82). The five pages of the article are available below with kind permission of the WFA.

INTRODUCTION

British involvement in the Somme did not end with the armistice. British towns and cities became involved in ‘adoption’ schemes to provide help for the devastated battlefield. This article is a case study of the link between Albert and Birmingham. In 1914 Albert was a small Picardy town of about 8000 inhabitants situated on an old Roman road between Amiens and Bapaume. The Ancre flowed under its basilica. It had failed to become a ‘Lourdes of the North’ for pilgrims impressed by a medieval legend despite the desire of Pope Leo XIII who coined the term in 1898.

WARTIME ALBERT

Although almost captured by the German advance in September 1914 for most of the rest of the war Albert was only two miles from the front line. In March 1916 it came within a new British sector of the front line and as such had a vital importance as an administration, control, billeting and supply town. It also provided medical facilities. For British troops moving up or down the line Albert was always associated with the landmark figure and its associated legend of the ‘Leaning Virgin’ on the dome of its basilica dedicated to Notre Dame de Brebieres.

The future Brigadier-General James Jack was in Albert on 29 April 1916…

‘This red-bricked, or colour-washed town, considerably mutilated by bombardments, is occasionally under long-range fire. One shell has caught the church spire, bending the figure of the Virgin Mary as if it might topple down at any minute. Many of the streets are, however, little the worse for the War and there are quite a number of inhabitants still in the place’. (1)

On 26 March 1918 Albert was taken by the Germans during the Kaiser’s final offensive. Fearful that the Germans could use the tower of the basilica for observation it was knocked out by a British shell on 16 April. The virgin fell but the war did not end!

On 22 August 1918 Albert was recaptured by the 8th East Surreys. G.H.F.Nichols wrote…

‘Albert was ours again; but it was a tragically unfamiliar Albert in which the men found themselves in the glare of that day’s hot August sun. Streets, once picturesque and lively with the business of British military life, had become mere paths littered with rubbish, lined with stumps of walls and wrecks of buildings, and undermined in every direction with land-mines and charges. The basilica from which the golden image of the Virgin and Child had hung for so long was there yet, and its vast nave still dominated the town, but it had become a mere huge forbidding shell of red brick. In front of it lay a wrecked German plane, and here and farther on, near the Singer factory, dead British patrols; and everywhere were German dead. ….it was difficult not to feel , as one looked around the hideous wreckage of what once had been a pleasant, stately little town, that he (the Boche) had found a fitting tomb’. (2)

POST-WAR ALBERT

The appearance of Albert at the time of the Armistice is best summarised by a plaque in the Hotel de Ville which reads ‘Il ne subsiste alors que le nom, la gloire et les ruines’. Somme towns and villages were devastated by the war and post-war the inhabitants suffered acute privation. Martin Middlebrook writes… ‘The devastation was so complete that, at first, the French government planned to make the whole area into a national forest, without attempting to rebuild the villages or reclaim the land, but gradually, the former inhabitants started to return. Slowly the area returned to life. Working from old plans found at Amiens, the new villages and even most of the individual houses were built on the exact sites of their predecessors. Special labour units were sent to clear the land and fill in the old trench systems. It was feared that the numerous tunnels and dugouts might attract bandits so orders were issued that all the entrances to these were to be blocked. In the course of time most collapsed’. (3)

The national forest idea was linked to a possibility declaration that the area was a ‘red zone’ like the area around Verdun because it was too dangerous to rebuild. The inhabitants of Albert resisted this suggestion.

TIMES REPORTS

On 6 January 1919 Charles Adeane reported in the ‘Times’ on his tour of the Somme department. The headline above the story included ‘Ruined French Farms’ and ‘Need of British Help’. Albert was noted as one of six places that was ‘absolutely uins’. ‘They are cast down as if by an earthquake’. On 4 October 1923 Boyd Cable reported on his journey from Albert to Loos in a report for the Times. He began his tour in Albert…

‘Anyone who saw Albert today for the first time would be appalled at the sight of its many broken buildings and heaps of tumbled masonry; but those who knew the Albert of the end of the war must wonder rather at the large amount of it that has been rebuilt…If my eyes saw rather the rebuilding and rebuilt, the amazing progress of reconstruction, those who first see the area now can the better realise how much more awful and appalling was the appearance it wore in and immediately after the war. Albert is still badly broken up but at least it has retaken shape in streets and squares of new houses where many only knew a pave road bordered with a high wall of rubbish, stones and brick that had been cleared off the track through the town and thrown up to either side…….It would seem easier to pull everything down and rebuild it rather than “restore” it as some say is to be done’.

ORIGINS OF THE ADOPTION IDEA

Post-war large British towns and cities offered assistance to this damaged region and French communities were ‘adopted’ or twinned. In July 1920 Birmingham adopted the town of Albert. The general ‘adoption’ initiative appears to have originated in a shadowy organization called the League of Help. An important meeting was held in the Mansion House, London on Wednesday 30 June 1920 attended by Lord Mayors and Mayors of British towns and cities. The Times reported…

‘The meeting has been arranged by the British League of Help, which has undertaken to seek out for each war devastated town and village in France a British god-parent’ community to give it practical aid and sympathy in its reconstruction’. (4)

It was stressed that large sums were not needed as reparation was the responsibility of the German Government under the terms of the Treaty of Versailles. The Lord Mayor of Birmingham probably attended this meeting and took the idea to the General Purposes Committee of the City Council who approved the idea. Some other places had already adopted a town or village in France where

they acted as ‘marraine’ or godmother.

BIRMINGHAM - WHERE TO ADOPT?

The Birmingham Post reported on Wednesday 21 July 1920….

‘M.Marcel Braibant (French deputy for the Ardennes) was recently in Birmingham and was present at a garden fete of the Anglo-French Society. On this occasion he told a moving story of the pitiful condition of the devastated regions. In one place in particular referred to by him the inhabitants are living in acute misery; for want of beds they sleep on straw. Their one cry is for work, but to provide work…..one must have money to buy tools, machines and materials, and the unfortunate people have scarcely enough to buy food. What they want as well as money is sympathy and friendship’.

An editorial supported the suggestion of adoption as Birmingham had already contributed generously to a European Famine Fund. It had been suggested that a place beginning with the letter ‘B’ would be a suitable adoptee. The same issue carried a letter from Ethel Brooks, the chair of the Birmingham Anglo-French Society. She wrote….

‘We in this country who have not suffered from enemy invasion, and can still lookupon our beautiful country unspoilt, cannot realise the harrowing feelings of those who see only ruin and desolation around them. It is not sufficient for us only to sympathise with these afflicted people; we must render them practical help’.

Lady Brooks, a magistrate, was the second wife of Sir Arthur David Brooks, a wartime Mayor of Birmingham. The Birmingham Anglo-French Society existed by November 1918 and was probably modelled on an earlier London society. Each year the Birmingham group ran social activities, lectures, rambles as well as an annual dinner and an annual fete. In 1925 it had 320 members. In the early 1920s the French ambassador was its Honorary President and the Vice-President was the Vice-Chancellor of Birmingham University, Sir Charles Robertson.

BIRMINGHAM ADOPTS ALBERT

On 21 July there was also an informal gathering at the Council House to discuss proposals to put before a public meeting. Chaired by Lord Mayor William Adlington Cadbury, those attending included aldermen andcity councillors, members of the Anglo-French Society, the Chamber of Commerce, the Rotary Club, the Cosmopolitan Club and ex-Territorial and City Battalion officers. A committee was formed to take the idea forward and to identify the town for ‘adoption’ and its most pressing material needs. It was to be chaired by Alderman Sir David Brooks with Gerald Forty as the Honorary Secretary.Gerald Forty was a prime mover in the Albert adoption scheme. He was a Cheltenham-born businessman who had moved to the city in 1902 to manage a branch of his father’s firm. During the Great War (aged 37 at the outbreak) he became an officer in the Worcestershire Regiment and served at the War Office. He was also one of the founders of the City of Birmingham Orchestra. In 1934 he was awarded the Legion of Honour for his contribution to the Albert project. He died in 1950.

On Tuesday 27 July 1920 this Executive Committee met following the visit by a deputation to the headquarters of the British League of Help in London to find out which towns were available. They were told that Albert was the most suitable.

‘The reasons suggested in favour of Albert were its ruined condition, its association with the Birmingham “City” Battalions and other Warwickshire units, and the fact that its industries rendered it a town which Birmingham could readily assist, inasmuch as its chief needs are machine tools, agricultural implements and other metal and hardware goods”. (5)

DELEGATION VISITS ALBERT 1920

It was decided to send a deputation to Albert in mid-August. The delegation of six included a Birmingham Post journalist who wrote two detailed articles for his newspaper. He joined Mr and Mrs Gerald Forty, Mrs J.A.Kenrick, Lieutenant Colonel Crosskey and Lieutenant Colonel Deakin, who had commanded the 3rd City Battalion of the Warwickshire Regiment. They were greeted by M Piffre, the Mayor of Albert, who had owned the largest works in the town pre-war, employing 600, and produced ironwork for lifts and other branches of engineering. The Birmingham Post journalist recorded the ‘pitiable plight of Albert’.

THE ROYAL WARWICKS AND ALBERT

The link between the Royal Warwickshire Regiment and Albert cannot be fully established. Various battalions did fight on the Somme in 1916 including the Battle of Albert in the first phase and with men drawn from regular, territorial and New Army backgrounds. However, only 20 men buried in the three Albert Commonwealth War Graves Cemeteries (6) were from the Royal Warwicks out of a total of 1981. Let Private Joseph Hiley stand for all of them. He was in ‘B’ Company of the 10th Battalion and was the son of Mr and Mrs Joseph Hiley of 110, Deakins Road, Hay Mills, Birmingham. He died on 31 July 1916 aged 21. In addition the names of 1803 Royal Warwicks are on the Thiepval Memorial. (7) C.S.Collison has noted that the 11th Battalion was relieved in thetrenches by the 5th Royal Fusiliers on July 16 1916 and “returned to Albert and were billeted near the wrecked railway station”. It is very likely that many Warwickshire men passed through Albert or were billeted there at different times during the war. Ray Westlake indicates the following battalions passing through or bivouacing in or close to Albert….1/5th ,1/6th ,1/7th and 1/8th Territorials ,10th and 11th Service Battalions (8)

Punch October 4 1916

British cavalry in liberated Albert in September 1918. The Virgin has disappeared

Percival Bower, Lord Mayor of Birmingham, at a crucial time for the adoption

PERMANENT BIRMINGHAM AID – ALMHOUSES SCHEME

At intervals after 1920 gifts of money, clothing, bedding, building materials, seeds and gardening tools were sent from Birmingham to Albert. The inhabitants started to rebuild the town in 1924 and the following year the Lord Mayor of Birmingham, Alderman Percival Bower, Birmingham’s first Labour Mayor, inaugurated a scheme for a permanent contribution. The Birmingham Albert Adoption Committee met at the Council House on November 19 1925 under the chairmanship of the Lord Mayor. Gerald C. Forty, the Honorary Secretary, gave a resume of the work of the committee since 1920. Such work had been confined to the alleviation of acute distress for which £5000 had been raised in cash and kind. (9) Forty was still honorary secretary of the Birmingham Anglo-French Society.

The Mayor of Albert had reported to the Committee that his town was in need of almshouses for the necessitous aged poor and the cost, about £4000, was to be raised in Birmingham. The building would house eighteen people and a specification and plans had been drawn up. Alderman Bower now initiated a ‘shilling fund’ or Albert Memorial Fund. In his appeal to the people of Birmingham the Lord Mayor observed…

‘The spirit which prompted this act of adoption was one of gratitude that we had enjoyed immunity from the unspeakable ravages of war, and a desire to express, in a practical manner, our sympathy for the sufferings of our Allies. At that time Albert was a heap of ruins – scarcely a wall remained standing, not a single house was intact, and the small population were living in dugouts, cellars and hastily erected huts, suffering the greatest hardships, bereft of the very necessaries of life’. (10)

The proposed building ‘would also stand as a lasting memorial of our sympathy and serve to remind generations yet unborn of the friendship of this country for France’. Bower’s appeal also stated that ’there must be thousands of Birmingham citizens, many of whose sons are sleeping their last sleep in the cemetery at Albert’. This was, as explained earlier, an exaggeration.

FUND RAISING

The Lord Mayor hoped that the money could be raised by New Year’s Day, 1926. In early December the Lord Mayor reported early success to the Committee and some individual contributions were listed in the press. They included…

Lord Mayor £25

Cadbury Brothers £250

Alderman Lloyd £100

Alderman Clayton £50

Mr Archibald Kenrick £25 (11)

The New Year’s Day target was not reached. The Birmingham press of 19 January 1926 carried the Lord Mayor’s letter which revealed that the Memorial Fund remained open until the end of the month with only £1300 raised to date. His fresh appeal stressed ‘the effect which the possible failure of the appeal which might have in regard to the credit of the city both at home and abroad’. ‘The failure of the fund might be regarded as a stigma on our city’. He also noted that Birmingham was one of the last to fulfil its adoption obligations.

The Birmingham Post made its own comment in an editorial on the same day….

‘Several of these adoption schemes have now been completed and the and the new-built French towns possess visible and enduring memorials of their English foster-parents. Albert, however, has yet no such memorial gift of Birmingham…The sum is not a large one for a city of Birmingham’s importance’.

The newspaper reinforced the Lord Mayor’s new appeal as the intention of the shilling fund was that ‘citizens of the most moderate means should have the chance of helping’. Two days later the Birmingham Despatch reported a gratifying response with a further £500. New donors were listed including….

C.B.Holinsworth £100

Birmingham City Police £70

J.B.Brooks and Co £50

Neville Chamberlain £21

Birmingham Tramways Department £21

Kynoch Ltd £20

Colonel Howard Wilkinson £20

Birmingham Gas Department £20

Alfred Bird and Sons Ltd £10-10-00

By 27 January just over £2100 had been collected. Significant new donors included Mrs M.A.Bell, Latch and Bachelor Ltd, Birmingham Law Society and Lieutenant-Colonel J.L.Mellor. The sum inched upwards; £2420 by 3 February. Alderman Bower attended the opening of the Bakers’ and Confectioners’ Exhibition on 9 February and confessed that he had been bitterly disappointed by the outcome. He stressed the moral obligation of the 1920 commitment. Some substantial contributions now arrived. These included…

Bernard Docker £500

Colonel J.H.Wilkinson £200

Alderman and Mrs W.A.Cadbury £100 (second donation)

GEC £52-10-00

Hugh Morton £5

Austen Chamberlain M.P. £21

5th Battalion, Royal Warwickshire Regiment £11-19-06

NEARING COMPLETION

With funds nearing their target figure (500,000 francs), and sufficient at least for the construction of the almshouse building, Gerald Forty paid a visit to Albert and made arrangements with the Mayor for the preparation of detailed plans and specifications. Work would start almost immediately. A special meeting of the Albert Town Council was convened in his honour at which the Mayor, M. Emile Leturcq (1870-1930; Mayor 1925-30), proposed a resolution of thanks to the city, which was passed with great enthusiasm. Albert’s Mayor also hoped that his opposite number would visit Albert and lay the foundation stone. Forty had not visited Albert for over four years and he was able to witness… ‘wonderful progress….in the rebuilding of the town, which was practically non-existent except as a heap of ruins…The Municipal Offices, which in 1920 were housed in a primitive wooden hut, have now been rebuilt in the principal thoroughfare…The Cathedral, famous for its ‘leaning virgin’, is still a ruin, and bears evidence to the terrible devastation wrought by the German bombardment’.

The Lord Mayor now received a letter of gratitude from the French ambassador, M de Fleuriau, dated 3 March 1926. On 21 March the Lord Mayor received a copy of the resolution of the Albert municipality.

BIRMINGHAM DELEGATION TO ALBERT 1926

On Sunday 24 October 1926 a Birmingham delegation led by the Lord Mayor went to Albert for the foundation stone ceremony. The delegation members were…

Lord Mayor Bower

Ernest Sandford, Lord Mayor’s Secretary

Lady Brooks

Colonel Cecil Crosskey and Mrs Crosskey

Colonel Danielson

Miss Osborn

Mr Gerald Forty and Mrs Forty (Hon.Sec. of the Birmingham-Albert Committee).

M. Andre, French consul in Birmingham

The delegation was met at the Albert railway station by M.Emery, Prefect of the Somme, M.Klotz, senator and former minister, M.Lebercq, Mayor of Albert, the Municipal Council and Major Phillips, who represented the British colony at Albert. Everyone then went in procession through the decorated streets headed by the fire brigade, the gymnastic club and band, to the Mairie, where the Prefect decorated the Lord Mayor with the Legion d’Honneur. The fire engine presented to Albert by Birmingham was inspected followed by a banquet in the Mairie. The next stop was the Albert War Memorial where a wreath from the French citizens of Birmingham was laid by M.Andre. The Lord Mayor now laid the foundation stone of the new ‘pavilion’. That evening there was a dinner and concert. On the following day the Birmingham delegation visited the English military cemetery and toured the battlefields, including Longueval, Delville Wood, Pozieres, Thiepval and the Newfoundland Memorial Park. (12)

The annual report of the Birmingham Anglo-French Society for the year ending 31 December 1926 stated that…

‘It is a matter of history, worthy of mention in this report, that Birmingham’s adoption of Albert, which was originally proposed by this Society and formally undertaken at our Garden Party in 1920, was consummated at Albert on 24 October 1926 when the Lord Mayor – Alderman Percy Bower – laid the foundations stone of the Pavilion de Birmingham. This building, which is a Retreat for the Aged Poor, was presented by Birmingham as a permanent memorial of the Adoption’. (13)

In November 1926 the French Government conferred the ‘Legion d’Honneur’ upon Alderman Percival Bower in recognition of his work for the Albert Adoption Scheme. On 3 December the French ambassador, M de Fleuriau, visited Birmingham to formally present the insignia to Alderman Bower as well as Les Palmes Academiques for Lady Brooks and Gerald Forty. On 27 February 1927 Bower was knighted by the King.

ALBERT DELEGATION VISITS BIRMINGHAM 1927

Another visit took place in May 1927. Gerald Forty met the Albert representatives in London on Sunday 8 May and they travelled to Birmingham the same evening; they were greeted at New Street Station by Alderman Bower on behalf of the new Lord Mayor, Alderman A.H.James. Over twenty strong the Albert group included Mayor Leturcq, M.Meilhac, the Deputy Mayor, town councilors, officials and representatives of the manufacturers and tradesmen of Albert as well as a number of ladies. The following day there was a civic reception at the Council House and a wreath-laying at the Hall of Memory. At the former the Mayor of Albert stated that ‘a friendship born of suffering was imperishable’. A visit to the university followed. That evening a dinner was hosted by the Anglo-French Society. Lord Derby (14) was one of the speakers. On Tuesday 10 May the party visited Warwick and Stratford-on-Avon. The following day included tours of a municipal electric power station, the Dunlop company and the Bournville works and village of Cadburys. (15)

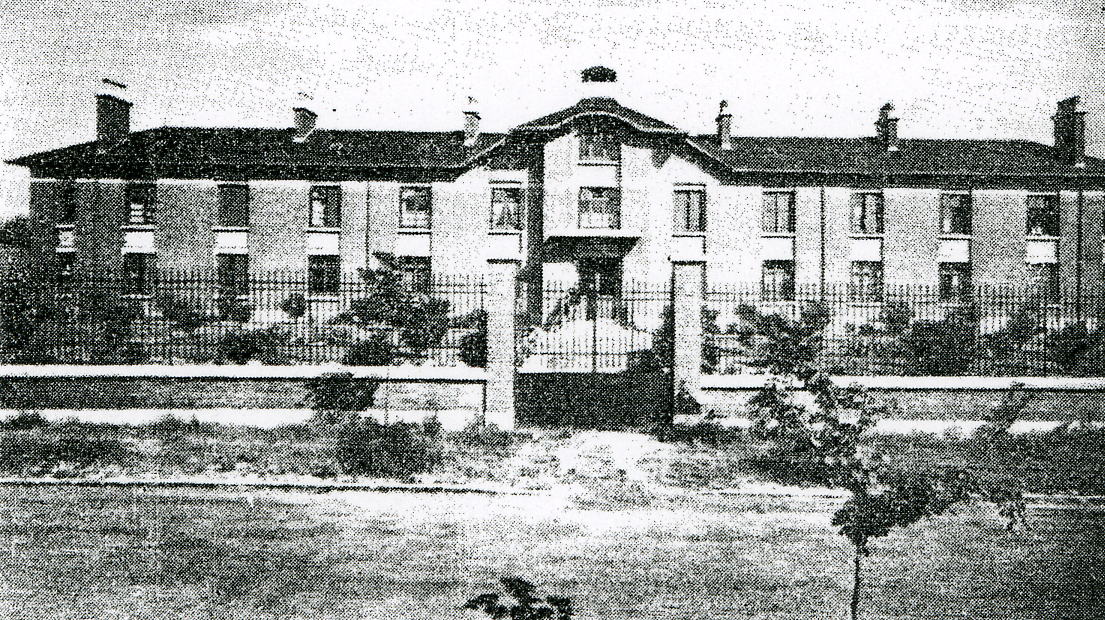

The almshouses were built and named the ‘Pavillon de Birmingham’. A street leading from the Square, where the main basilica was situated, to the main Bapaume Road was given the name ‘Rue de Birmingham’. Both were enduring symbols of the friendship between Albert and Birmingham.

THE BOND WEAKENS WITH TIME

However, it was a friendship that appears to have petered out as the Great War became a more distant memory and was overtaken by a new conflict. No evidence survives that can point to close official contacts between the two places after 1932 when the Mayor of Birmingham visited Albert at a time when President Lebrun visited the town to acknowledge its reconstruction. Martin Middlebrook suggests that the link was finally dropped in 1962 when the Communist Town Council of Albert made a new link to the East German town of Niesky, near Dresden. This link continues today with school exchanges. In the early 1980s a flicker of revival took place when the Mayor of Albert came to Birmingham and attended an Aston Villa football match. At the same time old soldiers made a visit to Albert. Veterans also appear to have maintained the Albert-Birmingham link. The annual reunion of the 1914-1918 veterans was held in the Birmingham Art Gallery to coincide with an exhibition entitled ‘I Was There’. In a letter to the Birmingham Post Edwin Gumbley, the Hononary Secretary, noted that the principal guest of honour was M.Claude Landas, Mayor of Albert. One hundred and fifty veterans attended (16) . Since 1976 Albert has been twinned with the Cumbrian town of Ulverston. Today the ‘Pavilion de Birmingham’ no longer serves its original function; it is now the offices of the Hospital.

CONCLUSION

How significant was Birmingham’s role as a godparent to Albert? The city of Birmingham probably contributed a sum of about £9000 towards the rebuilding of the damaged town; £5000 in cash and kind before 1926 and £4000 to build the ‘Pavilion’. In 2004 terms this total was worth about £332,000, a not inconsiderable sum of money. However, it does seem that Mayor Bower faced something of a struggle to reach the target figure with constant new appeals for support. In many ways Birmingham was a civic and middle class godparent to Albert with many donations from the ‘great and the good’ of the city although there were some workplace collections. In August 1920 the Birmingham Post reported that the James Watt Memorial Fund had already collected £13629; a similar amount in relative value to the Albert collection and over a shorter period of time.

The origin of the scheme with the Anglo-French Society also shows a class dimension. The annual purchase of the poppy for Armistice Day was already well-established and for the working classes of Birmingham the streets were a daily reminder of the scars of war. It was probably not easy to relate to an individual battle-scarred town in France even if it was the linked to the Somme. Albert itself had three other godparents which offered help, also commemorated with street names. Tientsin in north-east China had a French community; Bordeaux had avoided the physical damage of the battle zone; and the western Algerian town of Ain-Temouchent had many ‘pieds noir’ from Picardy.

REFERENCES

1. Terraine J (ed).’General Jack’s diary. War on the Western Front 1914-1918. Cassell. 1964

2. Nichols G.H.F. ‘18th Division in the Great War’ (1922)

3. Middlebrook M. ‘The First Day on the Somme’. Fontana, 1975

4. ‘The Times’. 19 June 1920

5. Birmingham Post. 28 July 1920

6. Albert Communal Cemetery Extension, Bapaume Post and Bouzincourt Ridge

7. Commonwealth War Graves Commission

8. Westlake R. ‘British Battalions on the Somme’. Leo Cooper. 1994

9. Birmingham Gazette 20 November 1925

10.Birmingham Mail. 28 November 1925

11.Birmingham Gazette 5 December 1925

12.‘TheTimes’ 2 October 1926

13.Birmingham Reference Library Local Studies reference to annual reports of the Anglo-French Society

14.Lord Derby, 1865-1948, Minister for War 1916-1918

15.’The Times’ 9 May 1927

16. Birmingham Post 12 November 1981

Emile Leturcq, Mayor of Albert, 1925-1930

The completed 'almshouses'

Menu for a dinner at the Queen's Hotel, Birmingham, May 9 1927