LIFE OF WILLIAM MILLS THE 'BOMB MAN'

WilliamMills was born in 1856 at Southwick, county Durham, into a family of what was then four children. His parents were David and Sarah Mills, both of whom were born in Monkwearmouth, Sunderland, in 1822. Southwick was one of the two Townships of Monkwearmouth on the northern bank of the River Wear, near Sunderland; it was an expanding industrial area with ship-building, glass-making and potteries. David Mills was described on the 1861 census as a 'ship’s joiner’ and the family home was at Wear Street, Southwick. In all William had five siblings…

Ann/Annie B born c1846

Sarah J born c1852

John George born c1854

George born c1860

Florence born c1866

In 1871 the family were still at Southwick but were now at 22, Camden Street, where some of the family were still to be found in 1881. David Mills had risen in fortune because the 1881 census described him as a ‘retired ship owner’ and the family now employed a domestic servant. David had owned and built wooden ships. William was not living with the family in 1881; all his siblings were still at home and unmarried. John was a commercial clerk, George a joiner, Ann and Sarah were drapers and Florence was a pupil teacher.

In 1891 David and Sarah Mills were described as ‘visitors’ at the home of David’s son-in-law, Friend Shield, who had married Sarah Mills. Friend was a farmer at Bowburn Farm, Cassop Cum Quarrington, Quarrington Hill. This was a coal-mining area about six miles south-east of Durham. William was also there as a ‘visitor’ with an occupation described as ‘engineer, manufacturer of boat gear and ship fittings’.

William ‘s earlier career was summarised in one of his later obituaries…

“After a private education in his native town he obtained a first class certificate as a marine engineer and went to sea. His varied experience included the arduous work of salvaging ships and the laying and repairing of submarine telegraph cables. Once he ran a blockade and witnessed in Peru and in Chile the spiking of the old-fashioned guns. His experience at sea resulted in his designing and patenting the Mills Patent Instantaneous Engaging and Disengaging Boat Gear, which in 1891, in competition with 15 other gears, carried off the ‘Fairplay’ prize of 100 guineas, the one and only prize of the kind offered at the Royal Naval Exhibition” (Birmingham Mail January 8 1932)

The Royal Naval Exhibition had been opened on May 2 1891 by the Prince of Wales in the grounds of the Royal Hospital, Chelsea. It was a major show which also featured a full-sized model of HMS Victory and the Franklin Gallery. Over 73,000 visitors attended its wide range of attractions. In his early life William had voyaged all over the world. His experience probably gave him the idea for his ‘gear’, his first patent. This also won the highest award from Mercantile Marine Service Association, the gold medal of the Liverpool International Exhibition and the highest award medals of the Newcastle International Exhibition and the World Fair at Chicago in 1893. It is likely that it was first exhibited at the Liverpool Shipowners’ Exhibition in 1886. The gearing was approved by the Board of Trade and it came into worldwide use on naval and merchant vessels.

William had left school at fourteen and had gone on to a seven year apprenticeship with Messrs George Clark, marine engineers of Sunderland. In 1884 he was awarded a first class certificate as a marine engineer. For a short unspecified time he was a draughtsman with the Central Marine Engine Works at West Hartlepool and assistant outdoor manager with Messrs J.Dickinson of Sunderland. A 1919 article cites how the boat gear was a life saver. The Chief Officer of the SS Drumberlie of Liverpool praised it after lifeboats were released quickly after the ship hit rocks in a storm and sank in ten minutes.

After the success of the boat gear William Mills turned his attention to the use of aluminium for mechanical purposes. It was well known as a lightweight metal but there was serious prejudice based on its reliability. Mills used exhaustive workshop and laboratory tests, including into alloys, and produced aluminium castings in 1894 which stood all the tests applied. It is not clear where he set up the country’s first aluminium foundry, probably Sunderland. William Mills, engineer, of Bonner’s Field, Monkwearmouth, was listed in the commercial section of Kelly’s Durham directory of 1897.The Birmingham works, the Atlas Aluminium Foundry, in Grove Street, Smethwick can first be identified in the 1908 Birmingham telephone directory. Wohler had extracted the metal from clay in 1827 and in 1856 the metal cost £3 an ounce. When Mills died in 1932 one could see at his Birmingham factory “hundreds of tons, chiefly in the shape of motor car crank and gear cases, cylinders for aircraft and all kinds of engineering requirements” (Birmingham Post January 8 1932).

It is not clear where William Mills was living on a permanent basis in the 1890s and the 1901 census does not help either. In that year he was a visitor at the Roker Hotel in Roker Terrace, Sunderland and was described as a ‘mechanic engineer’. It is possible that this was a business trip to his Sunderland works from a West Midlands home. He could hardly stay with his parents who had gone to live at 3, Worcester Terrace, Sunderland with William’s sister, Ann, and her husband, John Gamon, a Kent born art master. Later Sunderland directories would describe him as an aluminium founder and finisher at the same location. Even in the Sunderland area he appears to have regularly switched his home according to evidence of trade directories. In 1897 he was at 17, St George’s Square, Bishopwearmouth. In 1902 he was at Mayfield, Roker Park Road, Roker, a street for the well-off very close to the sea front. In 1910 he was at Northwood in Whitburn Road, Roker, and a similar area. The 1911 census shows that he was still at Northwood with his family although the address is now given as Cliff Park. In 1914 he is no longer listed as having a Sunderland residence.

In Durham in November 1891 William had married Eliza H Gandy, the widow of John Robert Gandy of Warrington. She was the daughter of W.Vincent Hodgson, a Manchester cotton spinner. John Gandy had died in late 1887 in the Ormskirk area at the age of 34. Eliza had married him in Ormskirk in 1882. One intriguing clue suggests some kind of Sutton Coldfield connection in 1901. In the census that year Eliza Mills, aged 43, was living at Claremont on the Lichfield Road there. No head of the household was cited suggesting that William was elsewhere. The household fits as there was a 21 year servant born in Sunderland and Eliza was described as born in Manchester. Intriguingly two children from Eliza’s first marriage were also there and had adopted the Mills surname – John H.G. born 1885 and Amelia G, born 1886. Both children were born in the USA as British subjects. On the 1911 census William and Eliza were living at Northwood; William was described as a managing director’. Also there was his step-daughter, Amelia Gwendolyn, whose place of birth was now given as Cincinatti, Ohio. There were also two domestic servants, aged 16 and 18.

In 1912 we can definitely locate William in the Birmingham area for the first time as Kelly’s Directory of Warwickshire shows him at Danesbury in Alderbrook Road, Solihull. The same address is also given on an American patent application dated July 20 of that year. Alderbrook Road had only been developed in the new century and provided detached homes for prosperous businessmen like William Mills. It was also convenient for railway access to central Birmingham.

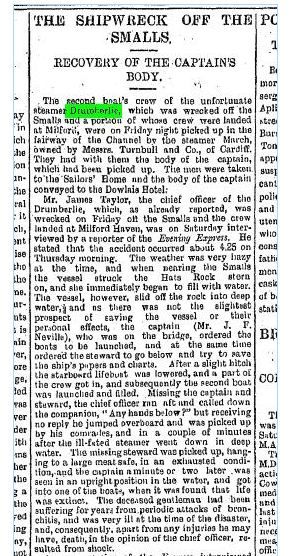

At some point William Mills turned his attention to the application of aluminium to golf clubs. He himself was a keen golfer and had joined the Wearside Golf Club around the year 1892. One of his obituaries in 1932 noted that “every golfer has heard of the Mills putter”. The web site of the British Golf Museum at St Andrews states that he “produced a whole range of aluminium clubs based on the long nosed clubs, also patented dual faced clubs, which were quickly termed ‘Duplex’ “. He also invented a telescopic aluminium stool. On July 20 1912 Mills applied for an American patent for “a new, original and ornamental design for the head of a golf club” granted on April 22 1913.

When Britain went to war in 1914 the demands of static siege warfare in the trenches meant a fresh look at the ‘grenade’, particularly as the German Army had their own in plentiful supply. In early January 1915 William Mills arranged with Major Banks of the War Office to help evaluate a Belgian hand grenade, the Roland. On January 26 Mills attended a trial with Albert Dewandre, a Belgian engineer who was familiar with the Roland grenade. The Belgian armed and threw four Roland grenades which Mills had fabricated for the trial, which went badly. Major Denn, the evaluator, rejected the Roland as unsafe and unreliable. On the following day Mills discussed the rejection with Major Banks. Banks made some vague suggestions about improvements and Mills soon came to believe that an improved Roland would serve the needs of the BEF in France. By the beginning of February William Mills had used his inventive engineering skills to devise a new hand grenade based on the Roland. He was able to turn something impractical into a workable grenade. The new ‘Mills bomb’ was successfully tested at Shoeburyness on February 20 1915.

The Birmingham Mail reported in 1932…

“Only those who remember the primitive bombs used in the early days of the war can understand the delight with which the Allied troops hailed the appearance of the Mills grenade. Previously our men in the front line had been driven to strange shifts to meet the bombing raids of the enemy. Empty jam tins, even, were brought into service and proved almost as dangerous and uncertain in the hands of their users as they were to the Germans. The new missile imbued the users with confidence and even a knowledge of superiority. It was pre-eminentlysafe and easy to handle” (Birmingham Mail January 8 1932)

The ‘Mills bomb’ as it became known was an essential ingredient in arming the infantry for the siege warfare of the trenches. The British Army went to war in 1914 with a percussion grenade derived from one used by the Japanese earlier in the century. They had a sixteen inch wooden handle and to throw them in a confined space was as likely to injure the thrower as the opponent. In particular, the backswing could easily connect with the back wall of a trench and then explode. Throwing by the head reduced distance. Various types of percussion fuse were used but none were satisfactory. The consequence was improvisation and the emergence of the jam pot or jam tin bomb made from discarded items and packed with explosive and ‘shrapnel’ of all kinds. The bomb was then sealed with a wooden plug and a fuse inserted. Mills bombs had a cast iron body filled with explosive. A tube which consisted of a detonator, fuse and percussion cap ran down the centre of the grenade. An external lever, attached to a spring, restrained the striker. A pin, in turn, held the external lever. The user heldthe grenade so as to depress the lever, withdrew the pin and threw the grenade. With no pressure on the lever the striker was activated and detonated the grenade after four seconds. The first Mills was the No.5, the ‘pineapple segments would assist fragmentation’. It was later adapted to also become a rifle grenade. The shape of the No.5 fitted neatly into the clenched fist. It also had the huge advantage of being able to be safely transported with the grenade separate from the time fuse which was armed when required by front line soldiers.

Although the Mills was the best of the wartime grenades it had numerous teething troubles. As late as mid-1916 there was still one accident for every 3000 grenades. Manufacturing faults could cause premature explosion and some pins slid out. The latter was probably the cause of the most well-known grenade accident of the war when Rifleman Billy McFadzean on July 1 1916 flung himself of a box of grenades which had fallen from a ‘shelf’. As the war developed platoons contained specialist sections which included bombers. In 1916 an improved No.23 Mark II version of the Mills bomb was introduced. It had already proved its use where the labyrinthine nature of trench defences made any advance without the clearing effect of hand grenades very difficult.

The War Diary of the 1/8th Warwicks described their attack on the Quadrilateral near Serre on July 1 1916….

“Enemy first line reached and passed very quickly as also was the second. Only in one or two cases were any enemy seen in the two lines. Having plenty of casualties from machine-gun fire in enemy third and fourth line. All the third line men were temporarily held up by machine-gun fire but took it by rushes. From this point the fighting was all with bombs along trenches. We reached our objective probably 35-40 minutes from zero hour and at once commenced consolidating and cleaning rifles….. By this time the next battalionwas arriving but had had so many casualties that they could not go through so helped consolidating. This happened with all battalions following us. Many times we were bombed from this position and regained it until bombs ran out. We had to retire to the third line parapet and hold on with machine gun and rifle fire. Parties were detailed to collect as many bombs as could be found (both English and German) and when we had a good store we again reached our objective. No supply of bombs were coming from rear so could not hold on and retired again. Enemy machine-guns and snipers were doing a great amount ofdamage all the while. Enemy artillery opened but fortunately their range was over, Held on to this position until relieved by a battalion from rear”.

Although William Mills can only be proved to live in the Birmingham area in 1912 the 1908 Birmingham telephone directory lists William Mills Ltd at the Atlas Aluminium Works in Grove Street on Smethwick 9. This was the first aluminium foundry in the country. A 1912 Birmingham directory describes the works as producing ‘aluminium castings of every description for motor car manufacturers a speciality’. In 1917 this aluminium founders works produced castings of ‘every description for motor cars, aeroplanes and general trades’. In 1919 he chaired the James Watt Memorial Trust on the centenary of the steam pioneer’s death. He was involved with the Council of the Birmingham Chamber of Commerce and various industry bodies. The 1920electoral roll lists William and Eliza Mills as living at 14, Church Road,Edgbaston next to the Deaf and Dumb Institution. In 1925 there was still aWilliam Mills (Sunderland) Ltd at Bonners Field.

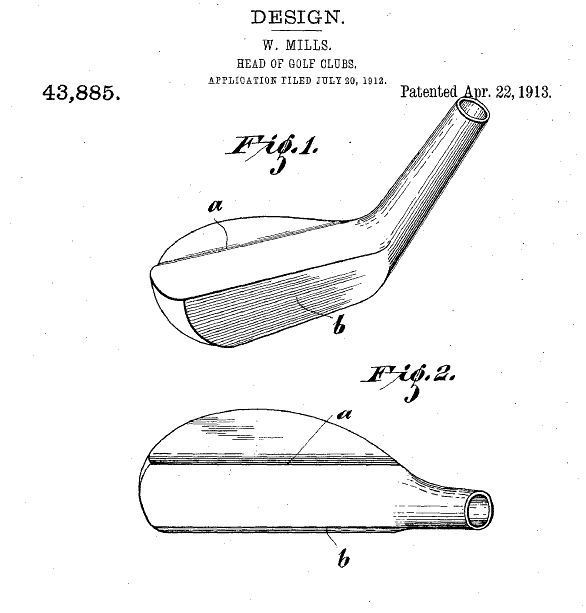

After William Mills had developed his grenade in early 1915 he opened a works to manufacture it in Bridge Street West in Birmingham which became known as Mills Munitions Limited. With other firms perhaps 75 million were produced during the war. His firm was given no preference overothers and probably made nearly four million of the total.

For his services to the war effort he was rewarded with a knighthood in June 1922 and received £27750 from the Royal Commission on Awards to Inventors. He failed in his expensive legal claim that he was not liable to pay income tax on that sumand often stated that he had lost money by the grenade. Just before his death he told an interviewer that he had lost £30000 on it.

He was a collector of pictures, china and antiques and a member of Moseley Golf Club. His wife Eliza died in May 1930; there had been no children from the marriage. She had been a member of the committee of the City of Birmingham orchestra andchairman of the Ladywood Women Unionists’ Club. William died at Edgefield, Broadoak Road, Weston-super-Mare, on January 7 1932 where he had gone for health reasons instead of his usual winter at his Riviera villa. He still owned the house in Edgbaston. A memorial services was held at Edgbaston Old Church in Birmingham where Canon Blofeld spoke of his ‘inventive genius’ and he was cremated. He was worth £37829 at his death which equated to about £1.26 million in 2005 values. In March 2002 his Knight Bachelor’s badge and War Service badge and an archive of correspondence were sold at auction.

Bibliography

OxfordDictionary of National Biography

Birmingham Gazette January 8 1932

Birmingham Mail May 3 1922

‘The Mills Grenade. The Mysterious Mr Mills’. Whitehall Gazette. 1919

Sunderland Echo March 14 2002

'British Hand Grenades’. David Payne. WFA. 2008

‘A Muse of Fire. British Trench Warfare Munitions, their Invention, Manufacture and Tactical Employment on the Western Front, 1914-1918’. Anthony Saunders. Phd. Exeter University.

Birmingham Mail January 8 1932 and January 11 1932

KEY TO PICTURES:

Western Mail May 4 1891

Golf head design patented in the USA in April 22 1913

Mills telescopic aluminium stool

A Mills company advertisement

Grenade workers at Frederick Mountford's Minworth factory

Checking the finished product at Bridge Street West c1916

Below Tyne Cot CWGC cemetery at sunset